Your Memories May Not Be as Reliable as You Think: Our Brain Constantly ‘Rewrites’ the Past

Researchers from the University of East Anglia in the UK and the University of Texas at Dallas in the US have examined approximately 200 academic studies published in psychology, neuroscience, and philosophy to create a new framework for understanding how memory works.

The research reveals striking findings about how memories are stored in the brain and why they change over time.

“Our Brain Is Not a Computer Archive”

People generally think of episodic memory as a “mental archive” where events are recorded and recalled exactly as they happened when needed. However, Prof. Louis Renoult, the lead researcher, argues that this analogy is incorrect.

Speaking to The Debrief, Prof. Renoult states, “Memories are not stored like files on a computer,” emphasizing that the process is far more complex.

Every Recall Is an Update

According to the study, for a recollection to be considered a “memory,” it must be based on a real past event. However, what we remember is not an exact copy of that event.

Our brain combines fragments from the past with our general knowledge, past experiences, and even the current situation we’re in. Researchers call this process “re-encoding.”

In other words, every time we recall a memory, the brain updates and re-records it. This continuous updating process explains why memories become distorted, confused, or blurred over time.

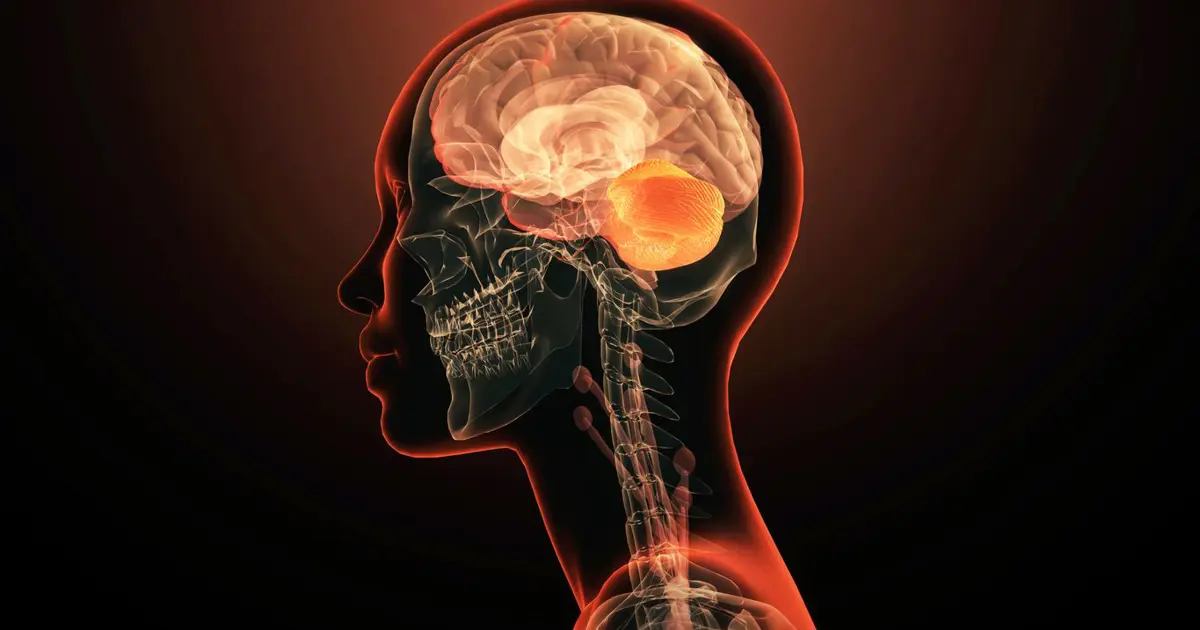

The Role of the Hippocampus

The research also highlights the role of the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center. According to the findings, some memory traces can remain “inactive” or stored unconsciously in the brain until triggered by an environmental cue—such as a familiar scent, a place, or a question.

Important Even for Courts

These findings are not just a matter of academic curiosity; they have profound implications for our daily lives, from learning processes to mental health.

Particularly in the legal system, the reliability of memory in decisions based on eyewitness testimony is being reconsidered in light of this research.

Researchers emphasize that understanding memory as “dynamic” rather than fixed will enable more accurate decisions in both psychological treatments and courtrooms.